Emeral Magic

Mixing joy and sorrow, a Celtic musical revival is sweeping the globe.

The music drifts out of some half-remembered Celtic twilight, echoing a thousand years of glory and heartbreak. Part ethnic folk, part New Age--inflected minimalism and part straight-ahead rock 'n' roll, it is hypnotic yet eerie, sophisticated in concept, yet primitive in appeal. Sing to it, dance to it or paint yourself blue and howl at the moon: the worldwide Irish musical renaissance is upon us.

Irish music? You mean the rum-tum-tiddle drinking and rebel songs made famous by the Clancy Brothers--and generations of barroom tenors? Rock stalwarts like The Cranberries, U2, Sinead O'Connor, Van Morrison and Elvis Costello, whose appeal transcends nationality? Or at the other end of the spectrum, the venerable Chieftains, whose 1995 album, The Long Black Veil, was the traditional Irish-music band's first gold record, their sprightly tin whistles, thumping bodhrans and wailing uilleann pipes blending harmoniously with the likes of Mick Jagger, Ry Cooder and Marianne Faithfull?

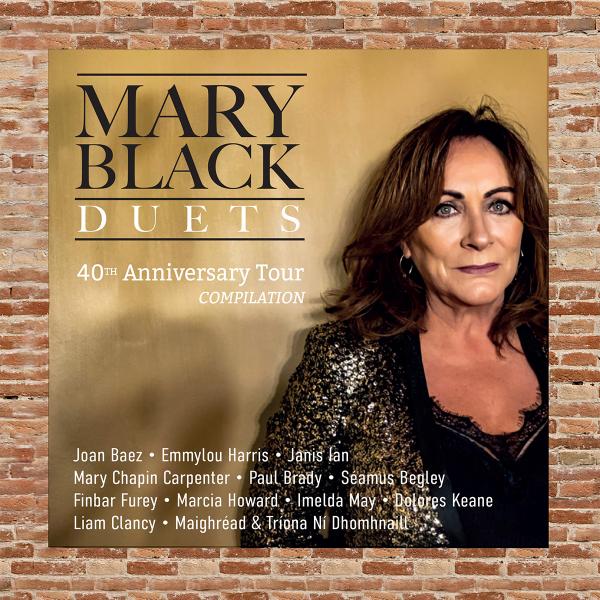

Think again. Welding traditional Irish tunes, forms and rhythms to rock and the evanescent modalities of New Age, a new group of Celtic musicians is birthing a terrible beauty that would make Yeats proud. Few of the performers are mainstream household names yet. But for sheer depth of talent, it's hard to beat the Irish, Scots-Irish and Celtic-American-Canadian performers whose music currently commands two-thirds of the spots on the Billboard World Music Chart. So say hello to Clannad, Enya, Maire Brennan, The Corrs, Mary and Frances Black, Christy Moore, Loreena McKennitt, De Dannan, The Boys of the Lough and a Hibernian horde of others, storming the battlements of the mainstream.

Why Celtic music? And why now? "Record listeners over 30 want to broaden their horizons, but they don't want to listen to the same stuff they heard when they were growing up," explains Atlantic Records co-chairman Val Azzoli, who discovered the red-hot group Hootie and the Blowfish (they're not Irish) and who recently created a sublabel called Celtic Heartbeat to showcase Ireland's rising stars. Older listeners "have stressful jobs," Azzoli continues. "They want music to chill out and relax, but they want music with style. This stuff has it."

Whether it's the hard-core folk appeal of The Boys of the Lough (the most rhythmically bracing of the traditional-music bands); the archaic musings of the Clannad gang, which includes solo spin-offs Enya and her sister Maire ("Moya") Brennan; Manitoba-born McKennitt's otherwordly vocalizing in a variety of international styles; the Black sisters' smooth pop sounds; or the angry social protest of Moore ("the Irish Bob Dylan"), the current Celtic renaissance offers something for everyone.

In the U.S., the Scots-Irish roots of country music have always been front and center--Irish country fiddling and Kentucky bluegrass are not so far apart after all. Texas-born folk diva Nanci Griffith, who considers Dublin her second home and has appeared on four Chieftains records, notes: "Texas music is heavily influenced by Scottish reels and jigs. As I think back, those sounds were all around, and those influences worked their way into my writing. There is something warm and genuine about Celtic music. Its roots are real, and people can sense that."

In the British Isles, meanwhile, the exuberant stage show Riverdance has been wowing audiences in both Dublin and London with an infectious blend of music and virtuoso step dancing; this month the show moves to Radio City Music Hall in New York City. In Australia, whose population is estimated to be one-third Irish and where the song The Wild Colonial Boy is a much loved anthem to the country's convict past, the popular Port Fairy Folk Festival in a tiny, heavily Irish coastal town boasts a large Celtic component, thanks to founder Jamie McKew. "Irish music's got all the energy of rock music, but also a kind of wild tribalism," notes McKew. Even in countries with few if any Irish immigrants, the music seems to resonate. In Japan, for example, albums of performers like Mary Black, long deleted elsewhere, are widely available, and audiences can be highly emotional.

Best known of the current crop is the charismatic, severely beautiful Enya, whose atmospheric and artfully crafted new album The Memory of Trees bolted from the gate at its release late last year. Born Eithne Ni Bhraonain (Enya Brennan, to non-Irish speakers) in County Donegal in 1961, Enya grew up as one of nine Irish-speaking children ("I had to go to school to learn English") in a passionately musical family. Her grandparents led a traveling band that played in small villages around Ireland. "They went from town to town, but they'd spend quite a bit of time in each place," says Enya. "Whenever Grandma, who was a drummer, got pregnant, she would wait there until the baby was born and then catch up." From this in 1980 sprang the nucleus of Clannad (the name means family), which consisted of Enya, her elder brothers Pol and Ciaran, sister Maire and their twin uncles Noel and Padraig Duggan. The manager, Nicky Ryan, is now Enya's producer.

Success came quickly for Enya, who left Clannad in 1982. With music for David Puttnam's film The Frog Prince and a bbc series called The Celts, her characteristic blend of Irish mist and mysticism came to the fore. Since then, Enya, 34, has pursued a hugely successful solo career (she makes her records painstakingly, playing all the instruments and overdubbing all the vocals), which has engendered some familial bitterness, mostly directed at Ryan, who is seen as the Svengali who broke up the group. Maire has also set off on a solo career, although her music is more pop oriented and less "mystical." Enya credits her background with the nature of her music. "There is an Irishness inherent in the melodies, and there's also a hint of melancholy continually, even with the up-tempo songs," she notes. "The melancholy comes from me, because the melody is very personal."

ATLANTIC'S NEWEST CELTIC phenomenon is another handsome Irish family act called The Corrs, who aim to strike a balance between Irishness and conventional pop-rock. Consisting of Jim Corr, 30, and his three sultry sisters--Sharon, 25, Caroline, 22, and Andrea, 21--the Corrs grew up listening to the traditional sounds that now flavor their modern beats. "You are what you eat," says Jim, the band's musical director. "But what we're doing is trying to take the music a stage further." Atlantic liked the Corrs' demo so much that the label asked David Foster (the Grammy-winning producer who works with Michael Jackson, Whitney Houston and Celine Dion) to produce their debut album Forgiven, Not Forgotten, which offers a mix from Erin Shore and The Minstrel Boy to more straight-ahead rock tunes like Someday and Love to Love You.

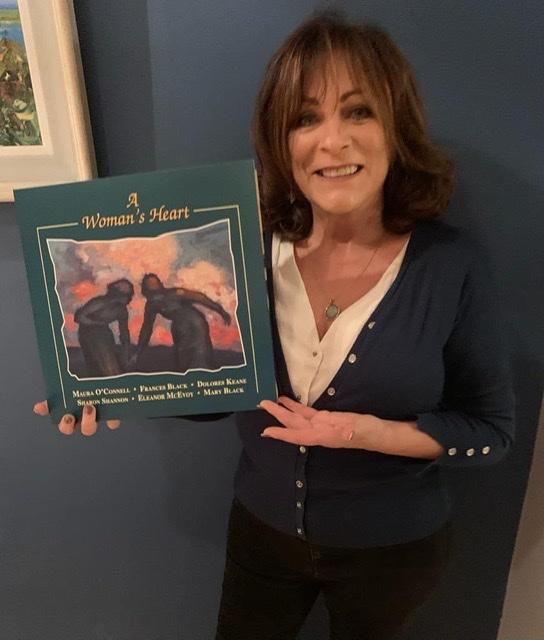

If Irish music is very often a family affair, then the most famous Irish musical family has to be the Blacks of Dublin. Mary, 40, has become the best loved and most popular female singer in Ireland, while her sweet-voiced sister Frances has lately embarked on a career of her own. "There is a passion about Irish artists because we've had a troubled past," says Mary. "We can cry when we sing, or we can laugh, and I think that's very much part of the Irish character." Black found her inspiration growing up as the child of a fiddle player and a singer from Rathlin Island. "My mother very much encouraged music in the house. Everyone would take their turn and do their bit--traditional Irish tunes," says Mary. At age 24, she made her professional debut on an Irish television show in 1980; a solo album and a stint as the lead singer of the folk group De Dannan followed soon after. A brief dabble in rock was succeeded by Black's fifth album, the poignant No Frontiers (1989), and the Black style was born: impeccable and stylistically catholic material, beautifully produced, smartly performed and sung in Mary's pitch-perfect, warm and resonant soprano. Some might dismiss her as a singer of "songs for swinging homeowners," but Black's international popularity is soaring with each new album.

"I think Americans relate to the Irishness in my music," she says. "Irish music has been influencing America for centuries. Country music is inherited out of a lot of Irish songs and ballads, and a lot of Bob Dylan's early stuff is very much influenced by traditional Irish songs. That sort of tossing over and back is still going on." Indeed it is: Frances Black covers four Nanci Griffith songs on her new album, Talk to Me.

Everyone agrees, though, that the current boom in Irish music would have been unthinkable without its godfather, County Kildare-born Christy Moore, 50. Irish bands from the Pogues to U2 acknowledge their debt to the fiery protest balladeer. Moore's work embraces the best of Ireland's traditions: native instruments (the plangent uilleann pipes on songs such as Bright Blue Rose and Quiet Desperation); a strong social conscience (Biko Drum); a crackling good way with a humorous narrative (St. Brendan's Voyage). A true son of Erin, Moore has a literary explanation for Irish music's popularity. "I think it's the way we use the English language," he says. "Irish people use it in a very interesting and colorful way."

Moore, too, got his first musical training at home, from his singer mother. "She sang political songs, hymns, light opera, whatever took her fancy." At age 6 he made his first stage appearance, and by 16 he knew music was to be his life. Cutting his teeth in swinging London during the heyday of the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, Moore returned to his Irish roots via the Clancy Brothers ("as exciting as rock 'n' roll, and yet it was Irish") and joined the folk circuit back home. In 1971 he formed the influential folk band Planxty, which lasted five years until Moore struck out on his own. Caught up in the Irish civil-rights movements, he made protest music his own, penning a series of scathing songs that decried colonialism everywhere. "I became dissatisfied that nothing was being written to comment on what was going on," he explains. But anger can translate to hostility. "If you're out on stage singing angrily, people tend not to listen." As Moore mellowed, his songs became more universal, limning the sorrows of the involuntary Irish emigrants in Britain, Scotland, Australia and America, turning one nation's tragic history into the story of all mankind.

"I like musicians who are sincere about their work, and I think in the long run those who enjoy longevity in their popularity are those who sing or play from the heart," says Moore. He could be speaking for all Irish musicians. "If your ambitions are for the sake of success, the audience will see that, and success will be very fleeting. But if you're seeking to express deep feelings in your work, you're in for a longer ride." It's a voyage audiences the world over seem happy to undertake.